Black space-making, bean pies, community, Harlem, history through architecture.

In "Mapping Malcolm," author Najha Zigbi-Johnson invites readers to view Malcolm X’s enduring legacy through the lens of Harlem. It’s a powerful exploration of Black space-making, community building, and global resistance, with Zigbi-Johnson weaving elements of history and neighborhood to contemplate Malcolm’s vision for justice, liberation, and how those teachings resonate in the present.

By Najha Zigbi-Johnson, as told to Ghetto Gastro

After grad school, I had the opportunity to work at the Shabazz Center, which is housed in the Audubon Ballroom, where Malcolm X organized his last political project, the Organization of Afro-American Unity. It’s also where he was martyred in February, 1965. Back in the early 90’s, the Audubon Ballroom was almost torn down and it took the community and specifically Malcolm X’s late wife, Dr. Betty Shabazz and her family stepping in to say, “No, this is an important part of our history. This is an important reflection of Brother Malcolm’s legacy. This building needs to be kept open and available for us to use as a site for contemplation, education and community organizing.” Since his death it’s become a sacred pilgrimage site, if you will.

Having this opportunity to work, learn about, and steward the legacy of Brother Malcolm and Dr. Betty Shabazz opened a whole world for me, particularly in terms of how I understand social movement history alongside Black contemporary art and culture production. Together, I see this as an exciting way to engage with new generations of people.

While working at The Shabazz Center, I was offered a fellowship at Columbia University to think through the preservation of the Audubon Ballroom and Brother Malcolm’s community-based legacy. During this time, I thought a lot about the physicality of Audubon Ballroom: What does it mean to steward not only a philosophical legacy, but also a physical site and structure?

I became curious about how we rearrange the relationships and dynamics between people and institutions so they might better reflect Brother Malcolm’s political vision of anti-imperialism. During the fellowship, I really asked myself what it meant to be “in right relationship” with my community. That led me to Mapping Malcolm, which is ultimately a way to think about the spatial legacy of Malcolm X.

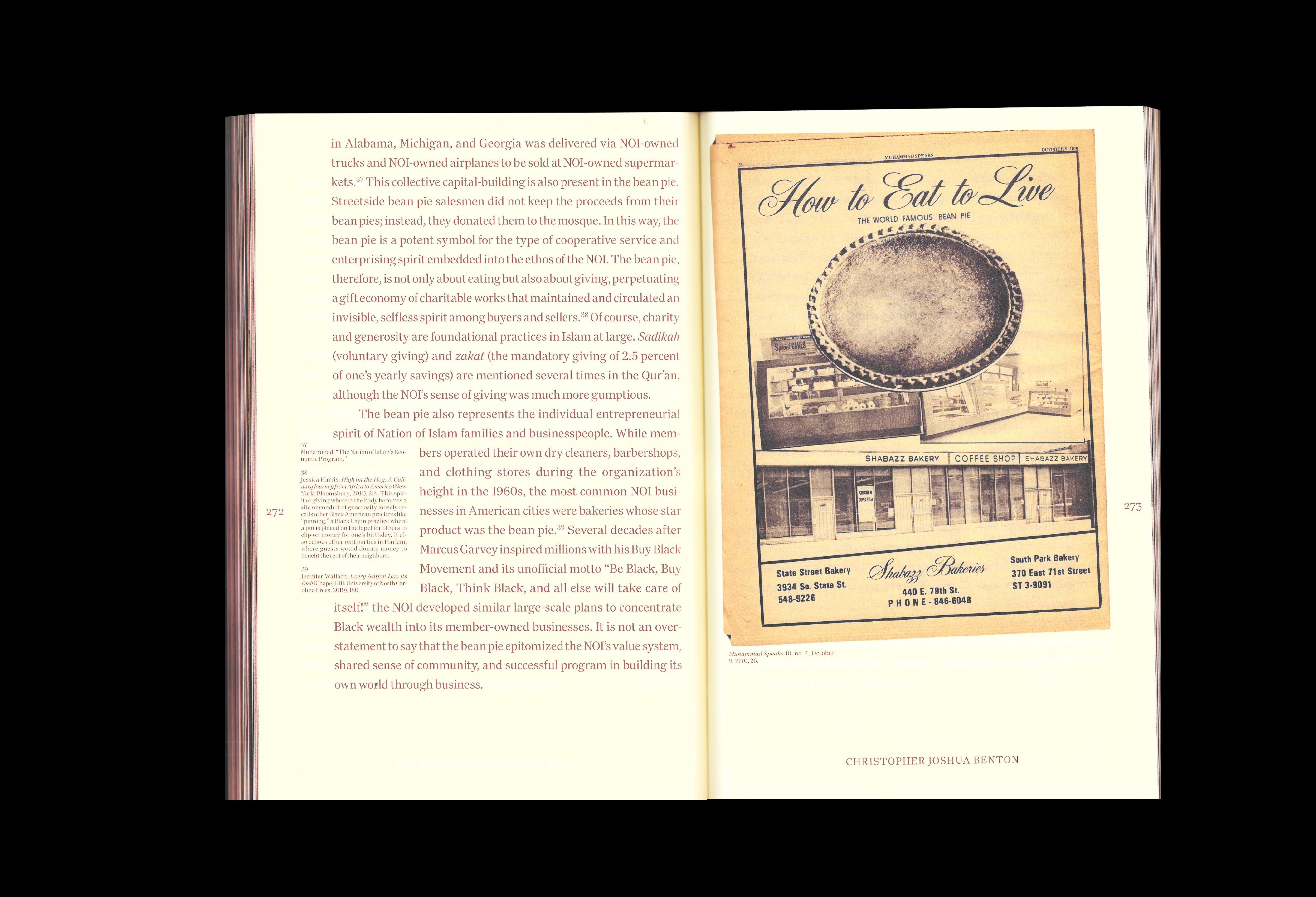

I grew up in Harlem, off Malcolm X Boulevard just two blocks from Temple No. 7, where they sell bean pies and copies of The Final Call. Growing up, the way I understood Malcolm X was the way I understood my community. Our history is imbued in the physicality of our neighborhood and cityscape. I wanted to tell a story about Malcolm X’s political, cultural, and religious vision that centered Harlem while also connecting us to the global diaspora in new and exciting ways. I wanted everyone to be able to find themselves in this book.

Mapping Malcolm offers readers many ways to get to know Malcolm X and this legacy through cultural history and through a new exploration of the built environment. The book includes pieces by folks who understood how Malcolm played jazz music before his speeches while part of the Nation of Islam—and how that communicated a sort of diasporic internationalism—as well as essays like Christopher Joshua Benton’s beautiful piece on eating bean pies and the foodways of the Nation of Islam.

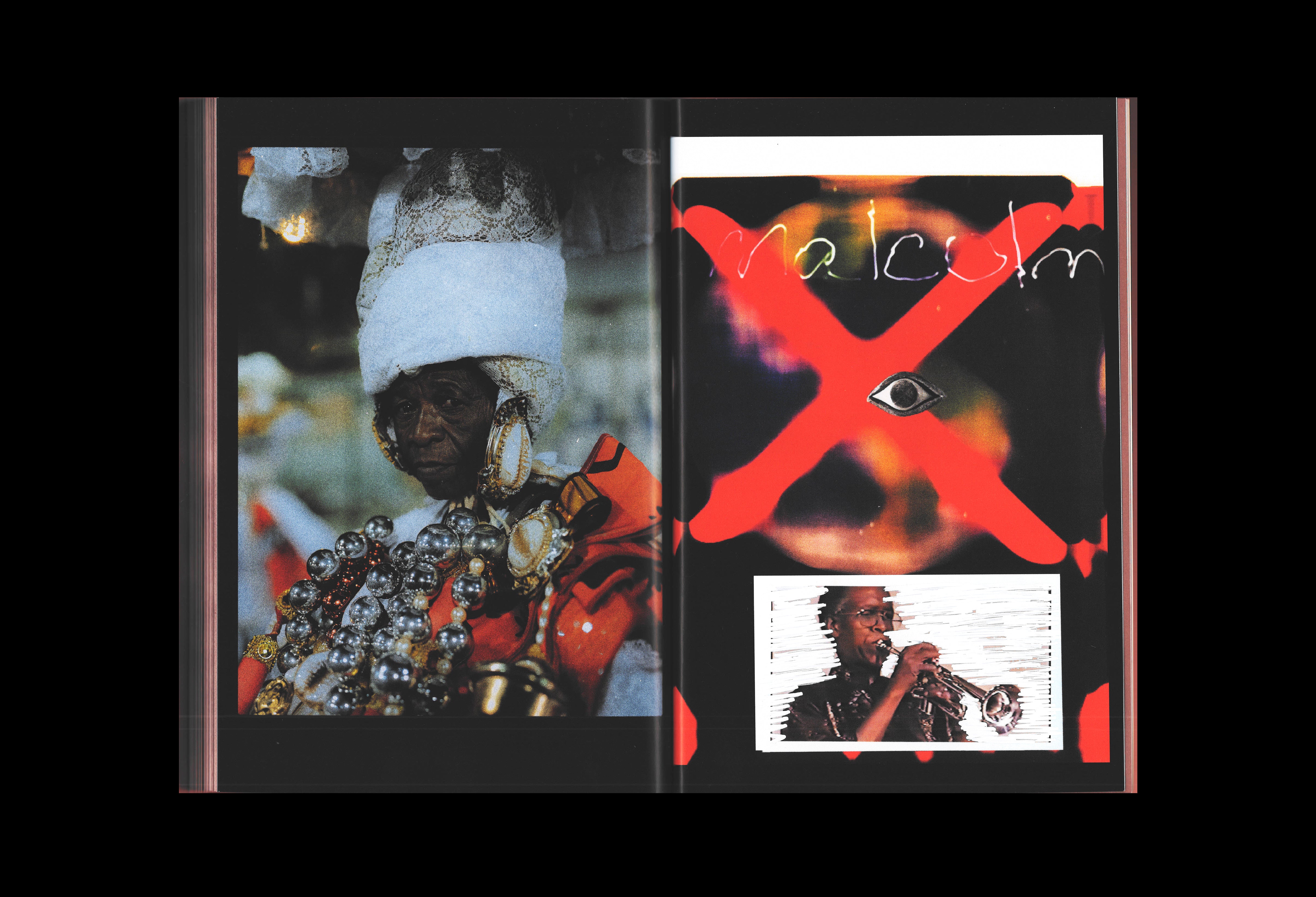

The book features a range of contemporary art, critical conversations, essays, playlists, and poetry, all as ways to reintroduce people to Malcolm X. This year feels particularly important because it’s the 100th anniversary of Malcolm X’s birth and the 60th anniversary of his martyrdom. Given the political climate we’re in, it feels particularly important that we reflect on and understand the wisdom that he shared. Especially now, his words are resonant because truth and wisdom endures all time.

"I’ve lived in Harlem for over 20 years. This neighborhood feels like a reflection of my soul. It's my home and the community I’m most deeply embedded in."

I’ve lived in Harlem for over 20 years. This neighborhood feels like a reflection of my soul. It's my home and the community I’m most deeply embedded in. It’s radicalized me, helped me understand politics, structural racism, and inequity. I also feel that the possibilities imbued within Blackness are reflections of our culture, history, music, foodways, spirituality, and religion. So in this sense, Mapping Malcolm is absolutely a love letter to my community: to the youth and to the elders. It’s also an invitation for people to exist in a type of freedom that says we have complete control over who we are, how we live, and how we want to be in community with one another.

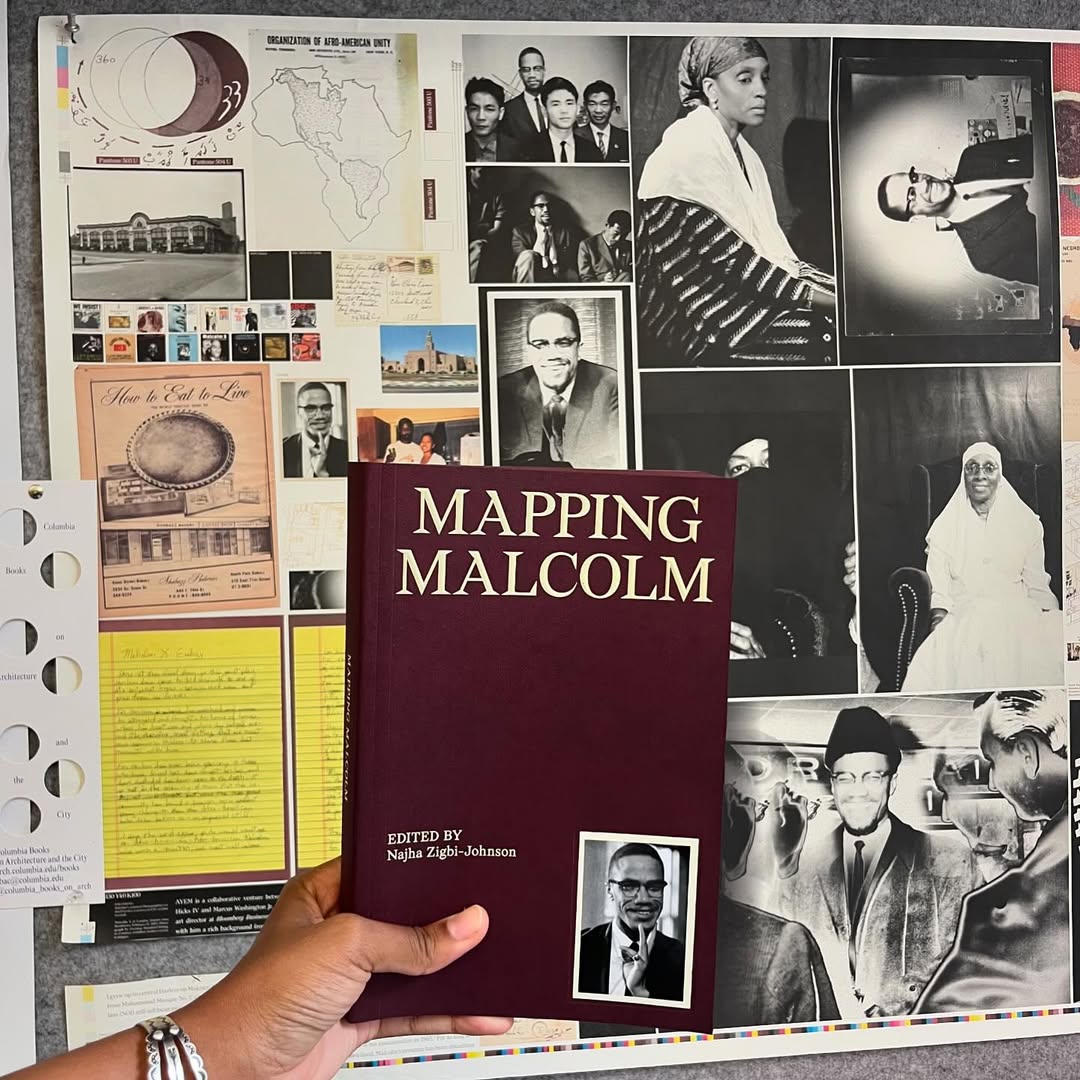

Part of how I love, honor, and understand Malcolm X is by recognizing that he was a creator. Yes, he was a philosopher and a religious leader, but he was also someone who listened to jazz, wrote poetry, loved art, and had a powerful photography practice. I think a lot about the aesthetics of his political vision and in so many ways, it informed the design of the book. For example, the burgundy on the cover of Mapping Malcolm reflects the burgundy of the old Nation of Islam temple awning on 127th Street, which I passed every day growing up. The circular crescent moon and Arabic wording that you see throughout the book is a riff on the original Organization of Afro-American Unity logo which, when translated reads “From Darkness to Light.” An original image of the flyer is also in the book and it’s amazing.

"Part of how I love, honor, and understand Malcolm X is by recognizing that he was a creator."

Even the color of the paper reflects this old ephemera. I wanted to show people that Malcolm had an artistic and aesthetic vision, because he was so committed to expansiveness and love. So much of how Malcolm is understood is erroneous: that he was hateful, divisive, the opposite of Martin Luther King. But he was unabashed and clear about his love, not just for Black people, but for so many experiencing oppression and inequity under imperialism.

Fully honoring Malcolm X and his vision for human expansiveness means honoring not just his words or his religious views, but also the culture and art embedded in his vision. Growing up in Harlem, I’ve experienced so much of that culture and art, and I wanted to reflect it in this love letter to my people.

Read more about the impact of Malcolm X in Najha Zigbi-Johnson’s new book, Mapping Malcolm. Available now.